S. stipatus

Found in the iron-rich cedar swamp waters of Cape Cod

Stentor are large ciliate protists that are found all across the world, in nearly every type of fresh water environment. Despite being unicellular, Stentor can grow as large as 2-3 millimeters, making these organisms large enough to see with the naked eye. Furthermore, these single-cell organisms exhibit strikingly complex behaviors and are capable of non-associative learning, complex decision-making, food selectivity, among much more. Our lab is interested in pursuing cell biology, behavioral, genetics, and phylogenetics research in these fascinating organisms.

Complex unicellular organisms like Stentor provide a unique opportunity to study the molecular and cellular mechanisms behind organismal behavior and other organismal processes like wound-healing and regeneration. Because the organism is a single cell, Stentor cellular processes directly result in the complex behaviors and processes of the organism. As an example, multicellular organisms generally rely on complex multicellular systems to maintain homeostasis and adapt to their ever-changing natural habitats. In order to thrive in aquatic ecosystems Stentor must also be equipped to adapt to the environmental changes that occur throughout the day and throughout the seasons. Unlike multicellular organisms, however, the Stentor cell must rely entirely on its own internal cellular systems in order to adapt and maintain its proper function. Our lab uses a combination of cell biology, genetics, molecular biology, biophysics, and computer vision to address questions about how the complex behaviors and organismal processes of the Stentor cell arise.

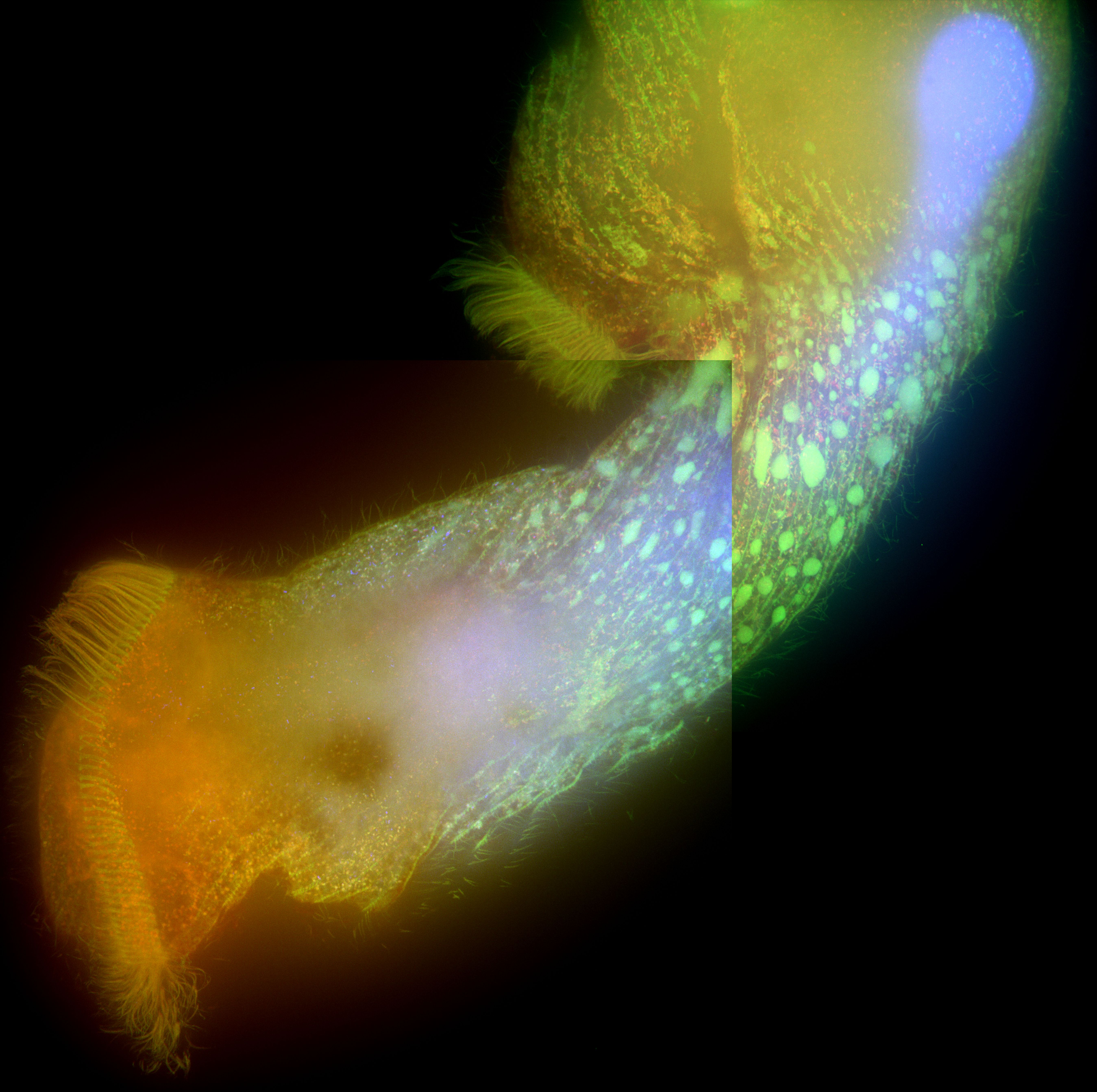

Stentor species feature a wide range of methods for detecting light and interacting with their environments. This includes species like S. coeruleus which has a photopigment stentorin that it uses to detect and turn away from bright light, S. pyriformis which has endosymbiotic algae that it uses to detect and swim directly towards bright light, S. stipatus which has both a photopigment and endosymbiotic algae and generally swims towards bright light, S. polymorphus which has non-obligate endosymbiotic algae that it uses to swim weakly towards bright light, and S. muelleri which is not known to contain any light detectors and exhibits no phototaxis.

Preliminary Findings: Several Stentor species are more likely to undergo cell division at night and exhibit stronger phototaxis during the day. These observations suggest that Stentor, like other Ciliates, may have a circadian clock that regulates key cell behaviors.

Our lab is currently exploring this potential via a combination of genomics (sequencing Stentor genomes), cell biology, and biochemistry.

Stentor are cosmopolitan, with at least 12 known species. Recently, molecular genetics has demonstrated that most previously identified species (around 30) are in fact conspecific variants of the main 12. Our lab is working to improve the phylogenetics and genomics of this genus in two main ways. 1) We are isolating new Stentor strains from around the US (with a major focus around Cape Cod Massachusetts), and sequencing their 18S (SSU) rDNA, along with a few other highly conserved genes to generate a more accurate phylogeny of the genus. In this way we have already identified two novel species, S. stipatus, a species that lives in the iron-rich waters of the white cedar swamps in Cape Cod, and S. hondawara, the first identified marine species of Stentor. 2) We are working to generate annotated macronuclear genomes for all newly identified Stentor species, as well as for any known species which has not yet been sequenced. Together, this work will allow us to better understand the evolutionary relationship between Stentor species and to incorporate forward genetics methods into future research.

Key Discoveries: We have identified two novel species: S. stipatus, a fresh water species tolerant of heavy metals and S. hondawara, the first identified marine species of Stentor.

S. stipatus

Found in the iron-rich cedar swamp waters of Cape Cod

S. hondawara

First identified marine Stentor species

Until recently, Stentor were generally believed to be exclusively fresh water ciliates. We have now identified one novel species, related to S. katashimai, that is uniquely adapted to a fully marine life, and a potential second species (unnamed; preliminarily verified by 18S sequencing only to be a relative of S. muelleri) that appears to live in coastal brackish waters between 15-30 ppt salinity. We are now working to sequence both macronuclear genomes so that we can compare these to the published genomes of fresh-water Stentors, S. pyriformis and S. coeruleus. We will use metagenomic and bioinformatics tools to analyze inherent differences between fresh water and marine species of Stentor in order establish unique adaptations that have primed marine Stentor for non-fresh water life.

Stentor roeselii has been demonstrated to exhibit a hierarchical decision tree of avoidance behaviors when presented with a noxious stimulant. Our lab has preliminary data showing that all Stentor species exhibit some variation of this hierarchical decision tree, though with some species-specific variation. Using careful control of noxious substance delivery in different stentor species, we aim to define a model that predicts stentor hierarchical decision-making. In the long-term, we will incorporate genetic manipulation to dissect the molecular pathways that affect and enact this hierarchical decision tree.

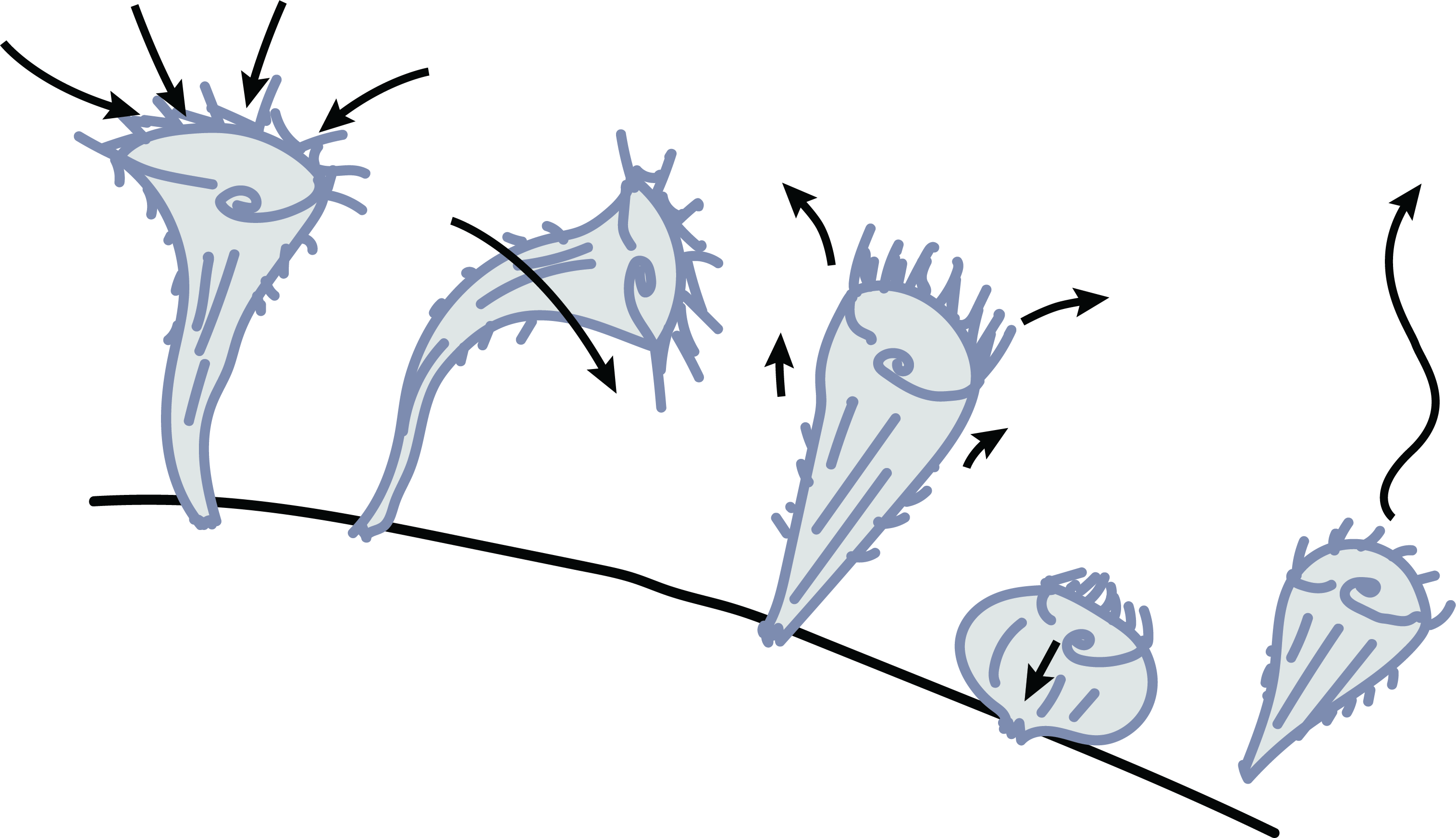

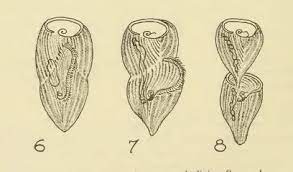

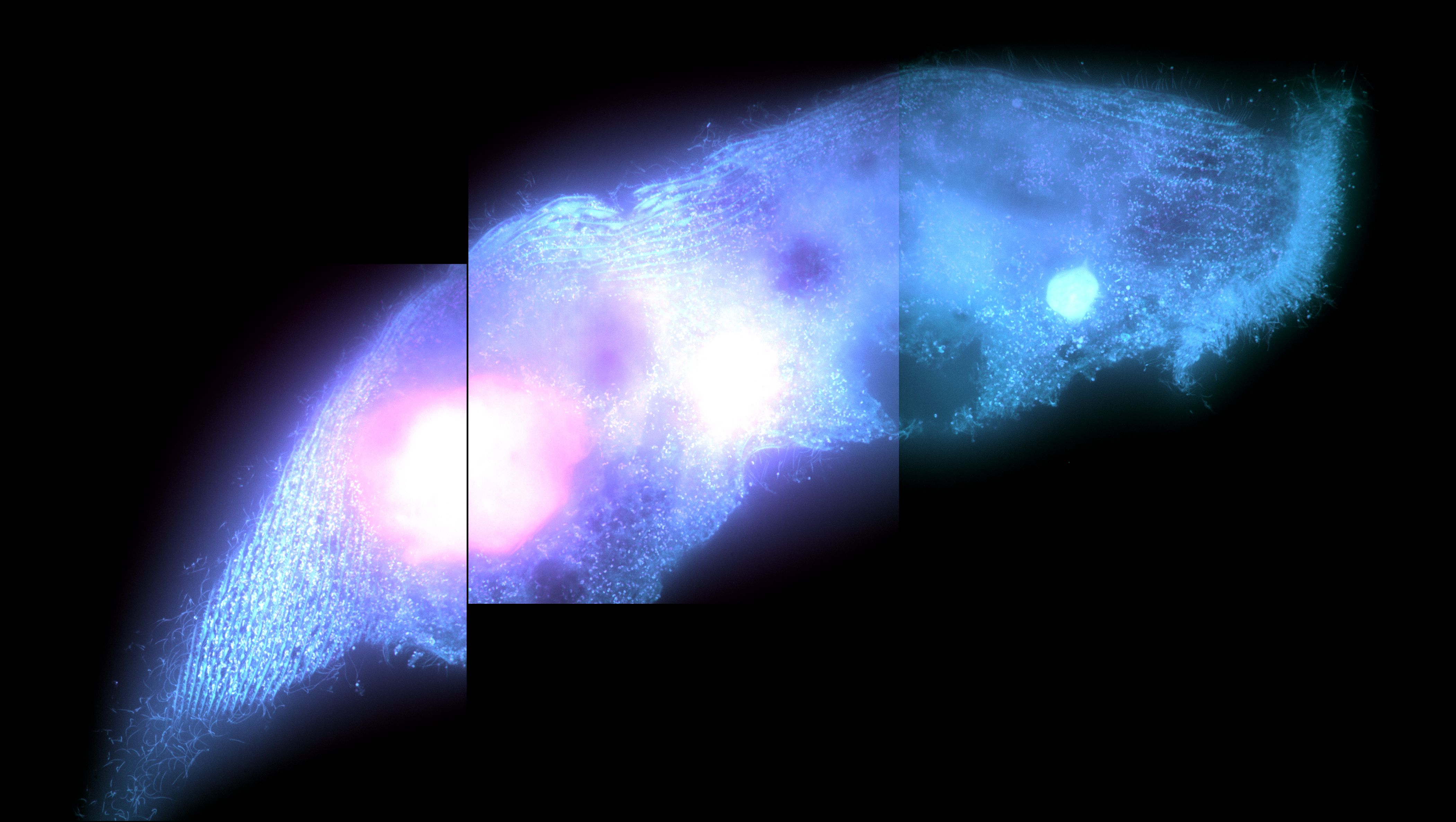

Stentor cell division, the primary mechanism by which Stentor reproduce, is a complex cellular event that requires careful orchestration of several processes. The macronuclear content of the cell undergoes significant restructuring and redistribution, while at the same time the cell begins to undergo constriction near its middle along the anterior-posterior axis. A new oral apparatus begins to form at the zone of contrast and migrates towards the top of the posterior daughter while the bottom of the anterior daughter begins to form a new holdfast in the region around the constriction. This leads to late dividing Stentor cells looking as if one cell is attempting to ingest the other.

Research Gap: Most of what we know about Stentor cell division comes from early research before fluorescent markers were available. Thus, it remains unknown how constriction occurs in this organism.

Stentor have actin and several myosin-like proteins, suggesting the potential for an actomyosin contractile ring. Our lab is using cell biology, genetics, and genomics approaches to decipher how constriction of the Stentor cell occurs during division.

Stentor pyriformis phototaxis is dependent on the endosymbiotic algae within it. We seek to describe how the algae modulates stentor behavior to make it turn towards bright white light with such efficacy. We are currently exploring particle image velocimetry (PIV) methods to describe changes in ciliary beating and flow patterns around the stentor cell body in response to asymmetric light source. In the long-term we will explore the genetic and molecular pathways that enable the algae within the stentor to make it turn towards white light.

2025 Virginia Tech. All rights reserved. | Site last generated: Dec 29, 2025